Where Does One Life End and Another Begin?

In my neighborhood, I’ve been seeing a placard headed “We Believe In,” listing “Science” among other beliefs, such as “Black Lives Matter.” These have popped up since the tragi-comedy in Washington has led to the sabotage of long-established facts in multiple realms. But science is not a belief system. It is a system of inquiry about the world through observation and experimentation, with the goal of establishing facts. Science cannot prove that Jesus is the Savior or Mohammed is God’s prophet.

Scientists develop theories, test them through observation and experiments that can be replicated, and make predictions based on the results. How they frame the questions they investigate affects their conclusions and leads to developments that shape who we are, how we think, and how our society works. The framework is built on a viewpoint.

Two contrasting perspectives seem to be gaining ground among natural scientists. One is dominant. It is based on the assumption that human beings are entitled to use natural systems for their own benefit, as objects or resources. That assumption is, of course, a belief. Scientists working from the second perspective consider us humans in context of many conscious beings. Contrary to viewing all natural systems as objects that can be manipulated for human uses, they think that humans must recognize the needs of others if we are to thrive. That too is a belief, an assumption.

Experiments have been going on for decades in transplanting organs from other species into humans. Recipients have not survived for long. In 1984, an infant known as Baby Fae, who was born with a defective heart, received a baboon heart, becoming the first human infant to be subjected to an interspecies transplant. She died a month later. Now attempts are underway to raise piglets specifically so their kidneys can be harvested.

The sanitized terminology is evidence of moral discomfort. We harvest grain, and other crops we plant, but surely not hearts. What this practice may lead to was presaged by Kazuo Ishiguro in his chilling novel Never Let Me Go, in which some human children are raised specifically to become “donors” of their body parts.

The second way of thinking is based on observations that various species are linked inextricably with other life forms by natural networks.

Canadian forest ecologist Suzanne Simard, professor at the University of British Columbia, discovered what is now known as the wood-wide web, a dense fungal network, or mycelium, by means of which trees communicate, share nutrients, and defend themselves. Her research and the book she wrote based on it, Finding the Mother Tree – Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (2015), have led to a growing understanding of forests as cooperative systems rather than systems where different species battle for survival. The German forest scientist Peter Wohlleben reported discoveries in keeping with those of Simard in his popular book The Hidden Life of Trees--What they Feel, How They Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World (1016).

Both authors have been slammed by colleagues and the timber industry as unscientific and accused of anthropomorphism, but both have also, over time, gained academic recognition, preceded by popular acclaim. What they have discovered resonates with many of us in our increasingly fragmented and compartmentalized world. We long for connection, and these scientists invite us to see interdependence in nature.

Simard discovered that fungi and roots exchange carbon, water, nutrients and defense signals through mycelial networks, masses of interwoven hollow threads that branch, fuse, tangle, and can grow in many directions at once. She found that Douglas firs traded nutrients with paper bark birches, for example. They ran short of sugar in different seasons, so they borrowed from each other, and paid back the debt when they had a surplus.

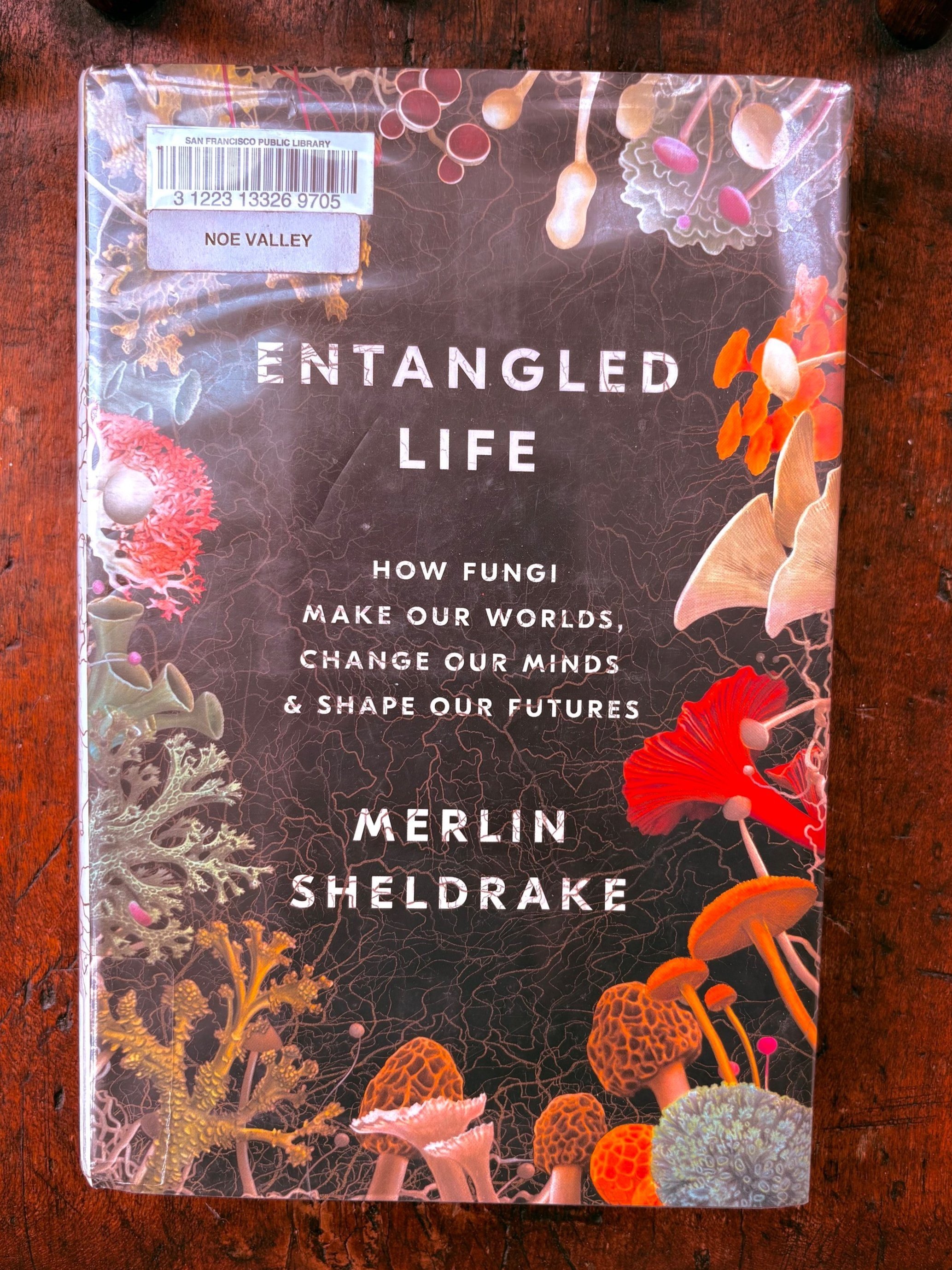

Merlin Sheldrake, a British biologist and mycologist, extends the concept of interdependence still further in Entangled Life--How Fungi make our Worlds, Change Our Minds, & Shape Our Futures.

Fungi are one of life’s kingdoms, alongside the kingdoms of animals and plants it is largely unknown. They range in diversity and size from microscopic yeasts to honey mushrooms, which are among the largest and oldest organisms in the world—one in Oregon spreads across more than three square miles and has been estimated to be 2000 to 8000 years old.

Everyone knows something about mushrooms, at least that many are delicious but some are poisonous, but the mushroom is only a tiny part of the organism, the fruiting body that produces spores, and many fungi don’t produce mushrooms that pop up from underground--the truffle, for example, which relies on its aroma to attract animals, including pigs and dogs, who dig it up, eat it and propagate the spores by excreting them.

Fungi are amazing. Some can break down rock, crude oil, polyethylene plastic. Some have been shown to be useful in cleaning up oil spills and nuclear waste. And some have the power to create visions in human minds, alter our sense of reality, and bring relief to people suffering from post-traumatic stress. They have been central to many religious ceremonies for ages. Yet very few fungal species have been studied, Sheldrake writes. Why?

Might one reason be that it’s scary to acknowledge that it’s not obvious anymore where one organism begins and another ends in the ever-changing dance of life on our planet? That has long been clear to practitioners of many spiritual traditions.

“As we learn that many organisms, even without central nervous systems, are capable of sophisticated behaviors” Sheldrake writes, “some of the vexed hierarchies that underpin modern thought start to soften. As they soften, our ruinous attitudes toward the more-than-human world may start to change.”

As research shows more and more clearly that organisms thrive only within relationships and natural networks, we might come to understand ourselves as members of a broad community of sentient beings. That understanding might even delay our own species’ extinction.

Mycelium growing outward from a spore. Redrawn from Buller, 1931.