This Little Piglet

Are there Limits to What We Can Do to Other Living Beings to Benefit Ourselves?

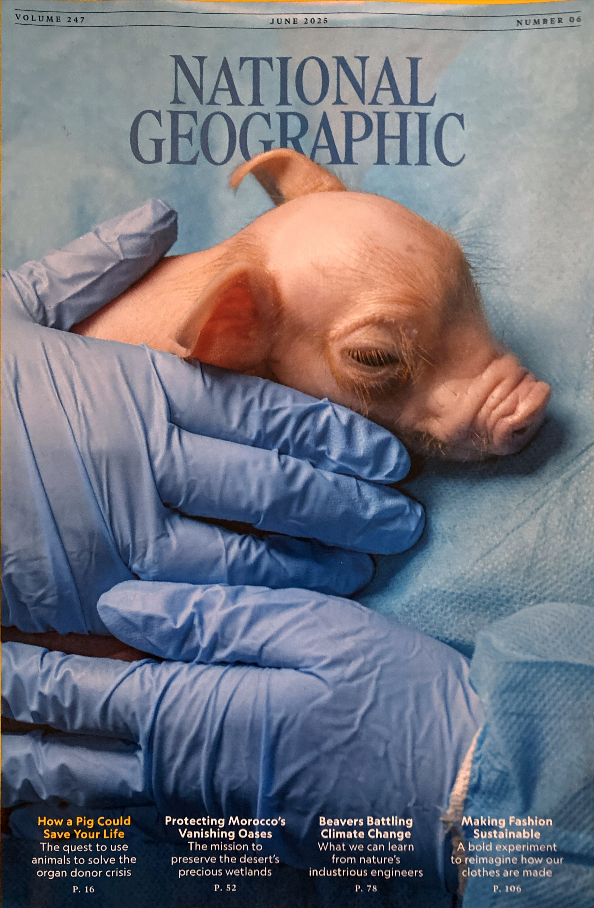

The cover of the June 2025 National Geographic shows an infant piglet held gently, one could say tenderly, in blue-gloved hands. It shocked me to learn that this newborn animal has been genetically engineered to be suitable to have its kidneys transplanted into a human being.

In news reports , experimental xenotransplantation , the use of organs from other animals to replace damaged organs in humans, is described as a major medical breakthrough that can alleviate the “global organ donor shortage.”

To me, it represents another step down the stairway to hell for humanity.

In March 2024, a man with kidney failure, who had exhausted all existing possibilities of treatment, underwent a procedure in which he received a kidney from a small pig at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The experiment was sponsored by a biotechnology firm backed by venture capital investors. The patient lived for almost two months, then died of heart failure. The firm obtained approval for three more clinical trials and has been preparing to produce thousands of cloned piglets to serve as organ “donors.”

Eventually, one expert in the field told the National Geographic, human donors won’t even be necessary. Other animals’ organs will be used.

Are there limits to what we can do to other living beings to benefit ourselves?

Every physician takes an oath to “Do no harm.” But it applies only to humans. “Modern medicine has been built on the suffering and killing of countless innocent animals from the ancient world to our own,” write Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy in Our Kindred Creatures- How Americans Came to Feel the Way They Do About Animals (Alfred A. Knopf 2024) “By 450 BCE, physicians in Alexandria used vivisection to differentiate between sensory and motor nerves.” Wasik is a journalist, Murphy a veterinarian. In their book they describe how attitudes toward other creatures changed over time in the United States.

Until the late 1800s, domestic animals and pets were considered to be private property, with their owner having the right to use them as he saw fit. If a man beat a horse struggling to pull a load that was too heavy, that was his business. By 1880, however, a passerby might well chastise him. Cruelty to animals was beginning to be recognized as a moral issue. Societies for prevention of such cruelty first appeared in Europe, then in the United States. In 1776 a retired Anglican bishop, Humphry Primatt, published A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals, which became a founding text of the movement to recognize that animals also suffer, Wasik and Murphy write.

The animal protection movement grew at the same time as the anti-slavery movement, the beginning of recognition that children were not property and that women had rights. People who had been considered subhuman (dark-skinned slaves) were redefined as fellow human beings. Eventually, this change of moral attitude and laws expressing it also affected the use of animals in medicine.

Legislation was passed in Massachusetts to forbid the killing of birds “for amusement or to test skill in marksmanship,” leading to a ban on trapshooting pigeons – the practice of luring hundreds of birds with a decoy tethered to a patch of ground spread with grain or salt, dropping a net over them, then releasing them so men could compete in killing as many as they could. This “sport “ helped to drive the passenger pigeon to extinction. Dog fights were banned and also rat baiting—setting trained dogs on rats.

Prompted by leaders in the animal protection movement, a federal law was passed requiring rest stops for livestock being transported long distances by rail to prevent deaths for lack of food and water .

In the late 1800s, the meatpacking industry consolidated. Livestock began to be transported by rail from much of the country to Chicago, to be slaughtered, processed, and packed for shipment in refrigerated cars at the giant Union Stock Yards. Chicago became known as “the Hog Butcher of the World.” In 1882 Philip D. Armour and Co. of Chicago was processing four million animals a year and employing 12,000 people. A fourth of Chicago’s workers were directly or indirectly employed in the livestock business.

The Union Stock Yards were hard to police for cruelty because of their size, isolation from the public, and incentives to employees to look the other way. Abuses reported included dumping animals still alive into boiling water. In 1958, the Humane Slaughter Act stipulated that animals must be “rendered insensible before being shackled, hoisted, thrown or cut.”

Abuse in meatpacking plants continues today, with a high rate of accidents injuring workers, low wages, and child labor. Many of the workers are recent immigrants.

In medicine, animals have long been used for research and education as though they were things, not living creatures, although few would now argue that they don’t feel pain. Jane Goodall and other scientists showing how close primates are to humans has led to a shift toward the use of other species in experiments. Pigs, for example.

“Despite being notably intelligent creatures, pigs tend not to be viewed with any particular reverence by most people,” the article in the National Geographic states.

But Is it moral to produce living creatures for the purpose of using their organs for humans?

Looking at the tenderly held newborn piglet on the magazine’s cover, I feel extreme discomfort.

This is a time when other scientists are discovering more and more ways in which various species are interconnected, and when natural systems, including rivers and forests, have been recognized by courts in several countries as having rights. So what about other sentient beings? Might they not have a right to life, even if it ends in being slaughtered for human consumption?

The terminology used in discussing interspecies organ transplants is distressing.

“Donor”—can a newborn engineered little pig be a donor?

“Shortage of donors” implies that people whose kidneys fail are entitled to a replacement.

“Harvesting organs”? We harvest grapes and wheat, but reaching into an animal’s body to extract an organ is surely something else.

In his 2005 novel Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro describes an elite boarding school where children are prepared to grow up to be organ donors.

Where is the bright line we cross only at mortal peril for our souls?